DNS Abuse: Everyone’s Problem

Lars Forsberg from iQ looks at the need for awareness of DNS abuse, especially of the new gTLDs, because with awareness comes the ability to act.

© allanswart| istockphoto.com

DNS Abuse is a topic that is on the tip of the tongue for many. Questions on how to define, categorize, and report this menace have been discussed at all levels, which in turn has spawned frameworks, initiatives and entire alliances. For the purposes of this article, I will be using the DNS Abuse Framework definition of DNS abuse.

“DNS Abuse is composed of five broad categories of harmful activity insofar as they intersect with the DNS: malware, botnets, phishing, pharming, and spam (when it serves as a delivery mechanism for the other forms of DNS Abuse)”

Another popular discussion to consider on this topic is the one surrounding responsibility. Whose responsibility is it to be aware? Whose responsibility is it to act? In general, there is very little actual contractual responsibility in regard to DNS Abuse.

The new gTLD agreement with ICANN includes a clause, Spec 11.3b, which requires the monitoring for threats, maintenance of reports on the number of security threats identified and the actions taken, and the report to be provided to ICANN if requested. However, Accredited Registrars are yet to be included in such a requirement and the discussion has not moved on very much in this respect.

But while there are currently no formal requirements, efforts are being made by community stakeholders to proactively minimise DNS Abuse, one such example being the Quality Performance Index (QPI) from PIR, the Registry behind .org.

At iQ, when working to help customers with DNS Abuse monitoring and mitigation, I consider the question of responsibility to be, if not irrelevant, then of less importance than the length of the discussion would indicate.

To make a lasting impact on malicious behaviour such as DNS abuse, it is my strong belief that there needs to be awareness throughout the entire ecosystem. Everyone involved in the delivery of a service should know what is going on, should promote this, and should share information with our direct relations: Registries with Registrars, and Registrars with Resellers.

With awareness comes the ability to act, and with a slight reference to the laws of nature, one could argue that for each type of malicious action, there is an optimal, opposite, and equal mitigating reaction.

This could, in and of itself, determine who should act, rather than a responsibility being handed out in a contract or, even worse, in national legislation where each country gets their own version of who should do what.

How big is the problem?

The first step to awareness might not be to understand your own slice of the problem, but to grasp the bigger picture. So, how big is the problem and how is it trending?

Let’s take a look at this using the Abuse Manager Threat Intelligence Feed. This data source is composed of meticulously monitored and vetted abuse reports, from well-known providers such as the Anti-Phishing Working Group and Spamhaus. The data source covers the same sources as the ICANN DAAR and several more.

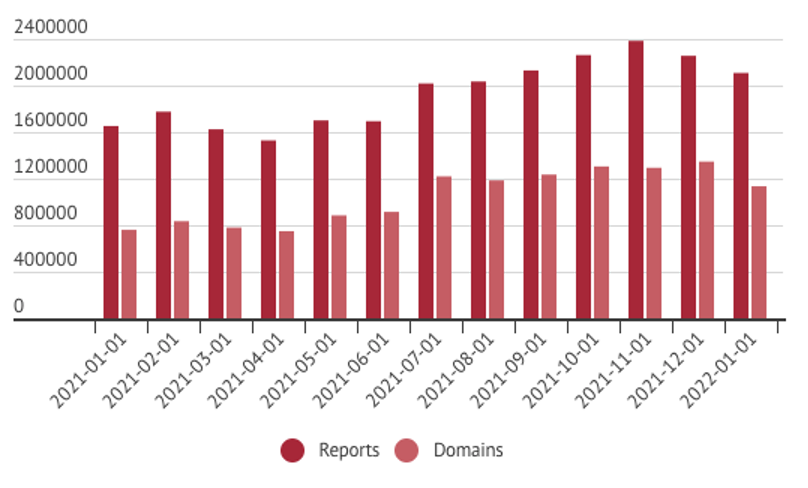

Graph: iQ Abuse Manager

On 2022-01-01, there were 2 108 649 reports of DNS Abuse, regarding 1 113 820 domain names in the data source. One year prior, on 2021-01-01, there were 1 652 691 reports of DNS Abuse, regarding 793 291 domain names. That is an increase of 27,5%, in just one year. Each report falls under the definition of DNS Abuse and each domain name is the smallest fully qualified domain name under the top-level domain name.

Today, roughly one in every three hundred domain names is indicated in a DNS abuse report from a reputable threat intelligence feed. Looking further into the data, the existence of reported DNS abuse is fairly consistent over top-level domain names.

In 2021, 901 distinct TLDs were featured in reported DNS Abuse. With roughly 1500 top-level domain names in existence, this would indicate that only 60% of TLDs had any reported DNS Abuse.

However, around 600 of the TLDs in existence are not available for registration, due to being a brand TLD or otherwise restricted. This means that the number of TLDs that are available for registration and have been featured in a DNS Abuse report during 2021 is at, or close to 100%.

The number of reports per TLD vary greatly, seemingly, due to price and popularity.

Some TLDs, especially those with a high price, low popularity, or a small target market often see less reported DNS Abuse than popular, low-cost domain names with a large target market. The relationship between $1 campaign domain names and DNS abuse is real, but that is worth an entire article in its own right.

One thing that the graph above does not take into effect is the speed at which the malicious behaviour is happening. During 2021, more than 16 million new DNS abuse reports were created, with an average of 45 000 reports per day.

The number of closed/removed reports is almost equal, standing at 44 000 reports per day. However, based on data gathered regarding these reports, and the domain name they regard, it would seem that only a small part of this is actually due to mitigation, with the overwhelming majority coming from the malicious actor moving on.

The average lifetime of a DNS Abuse report is 32 days, with mitigating actions closing a report after an average of 7 days, based on iQ customer data. In comparison, the average time for a report to be closed due to the malicious behaviour ceasing, without any detectable mitigation actions being taken, is 32 days.

This indicates that the number of DNS abuse reports closed due to active mitigation is very small, too small to move the average lifetime of a reported DNS abuse down even by a single day. This is not an exact science, as there are actions that could have been taken that do not decrease the lifetime of the abuse report. However, it is an educated estimation based on a large dataset, over a long period of time, compared to real actions taken by customers actively mitigating DNS Abuse.

In conclusion, I would say that there is not a lack of DNS Abuse reports to investigate, nor a lack of data on which to act, but there is a lack of awareness and a lack of action on the data available.

Is the pandemic a factor?

A frequently asked question when it comes to DNS Abuse is whether the ongoing pandemic has had an impact on these numbers. As noted, reported DNS abuse is increasing in general, and has been doing so for as long as iQ have been monitoring this data stream.

But, even so, the answer to this question would be yes. Some might be thinking of the initial reports of malicious behaviour when it comes to the news cycle and products that attracted significant interest, but that was not the factor that accelerated things.

Instead, the rate of growth in reported DNS abuse has been increasing during the pandemic due to the fact that more people are using the Internet for more things. The growth in reported DNS Abuse is not related to the keyword pandemic, the facemasks, or to the vaccines.

It is related to new services, new behaviours and the increasing number of people using the Internet to do their work, to communicate with colleagues, and to live the life that would otherwise have happened out amongst people. The business case for malicious behaviour became more appealing as a consequence of the pandemic propelling more people onto the Internet.

What can be done?

Whenever someone asks me what can be done about DNS Abuse in general, I always suggest the first step to be awareness. Get informed about the situation in general, and then get yourself informed about your own situation.

If you are struggling with finding information that relates to you and your company, I can recommend a free service called Abuse Stats. The service is provided by my company iQ, and is based on the same data source that I have used and referred to in this article. It can provide information on your current situation, and hopefully this will help you make an informed decision on your next steps. Whatever these steps may be, having a handy report delivered regularly to you, keeping you up to speed, is not a bad thing.

Graphics: iQ Global

If you are in a situation where you need to start thinking about how you mitigate DNS abuse, a situation in which most Internet-based service providers are, I recommend that you start by developing an Abuse Policy and a Abuse Management Process. The policy will make it easier to communicate up and down the line of services, and with end users that might be affected by your mitigation efforts. If you have to, or expect to need to scale your efforts, the process will be key to managing the work that you do.

Scaling is usually where most run into a problem. Investigating and mitigating DNS abuse is often manual and time-intensive work. A management system, be it a ticketing system or another tool useful for this purpose, is more or less essential.

Lastly, put your new policy and process to work. Take DNS Abuse seriously, investigate the reports of malicious behavior thoroughly, and take action. Your policy should determine if an action you can take is the optimal course of mitigation, and if it's not, make sure that you share information with the party that could take this action, whoever this party may be.

If you want to get a head start and not have to “reinvent the wheel” yourselves, iQ offers a service called Abuse Manager. It’s an easy-to-use SaaS platform that helps top-level domain registries, registry backends, registrars, resellers and other service providers that manage domain names receive accurate information about DNS abuse, as well as manage the work they do in mitigating the problem. My colleagues and I are also available to advise on matters such as developing a policy and process, or even managing your reported DNS abuse for you.

Lars "LG" Forsberg is an industry veteran with more than 20 years of experience from the registry, registrar and service provider side of the domain name business. He has broad experience from roles held in development, operations and management, within organisations such Loopia, the Swedish Internet Foundation (.se) and iQ.

Please note: The opinions expressed in Industry Insights published by dotmagazine are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of the publisher, eco – Association of the Internet Industry.