Data Protection for Connected and Autonomous Vehicles

Marco Müller-ter Jung from DWF Law looks at what data protection means for the development of new services in the area of the connected and autonomous car.

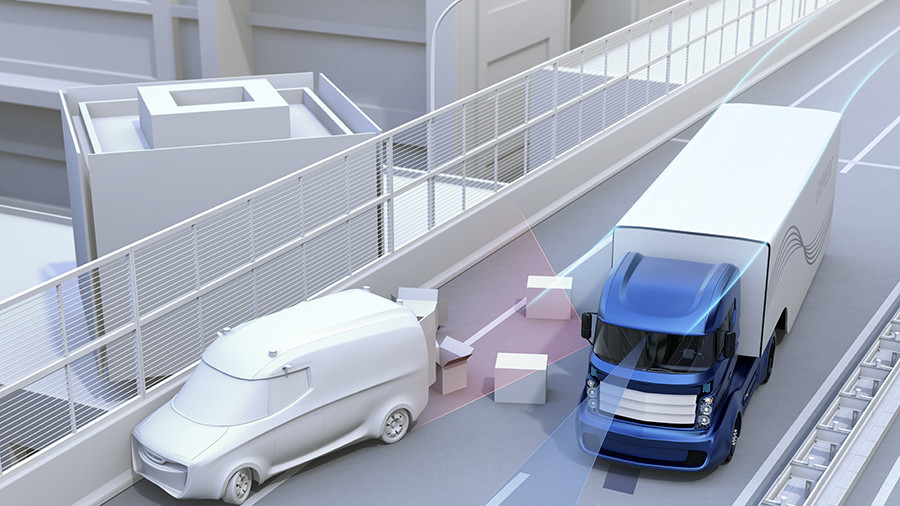

© Rost-9D | istockphoto.com

Why is data protection so important in the context of connected and autonomous vehicles?

The interconnecting and autonomation of vehicles means that vehicles collect enormous amounts of data, and exchange these with each other and with components of the transport infrastructure. Therefore, data protection law is of particular importance in the context of connected and autonomous mobility. This is because the breadth of data that is captured automatically is very large.

Not all data collected is actually necessary from a technical perspective to enable connected and autonomous driving. This applies, for example, to data that the individual driver/user enters for infotainment purposes or comfort settings. On the other hand, data for Car-to-X services and predictive diagnosis, and systems such as eCall, are collected – along with vehicle operating values, aggregated vehicle data generated in the vehicle, such as fault memory, number of malfunctions, average speed and consumption, and technical data, e.g. data generated by sensors.

Of all this data, a great deal will be considered personal data, so that the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) (and, in the future, for example, the ePrivacy Regulation, which has not yet entered into force) will then apply to connected and autonomous vehicles.

At the same time, the processing of all these data is not expected to be carried out by a single data controller who has to comply with the data protection requirements for the collection and use of personal data – rather, different data controllers will have access to different data.

In this context, numerous legal issues need to be clarified, such as who determines the purposes and means of the data processing, whether there are several joint controllers or parties who act under instructions from another party. For example, manufacturers, insurers, and car sharing providers may be joint controllers when they jointly determine the means and purposes of processing certain personal data.

At an early stage in the development of their products and business models, providers of connected and autonomous vehicles and systems will therefore have to analyze which data protection requirements have to be met in order to act in compliance with the law and to create trust in these new forms of mobility from the point of view of data protection law.

Can you give us some examples of when data from connected cars would be considered anonymous, pseudonymized, or would be seen as personal data? What is the consequence of each category of data for the data controller?

The decisive factor for the applicability of data protection law is that personal data are processed. “Personal data” means any information relating to an identified or identifiable natural person. This legal concept is to be understood very broadly. As a result, an identifiable natural person is to be defined as one who can be identified directly or indirectly, in particular by association with an identifier such as a name, an identification number, location data, an online identifier, or one or more specific characteristics.

One of the questions to be asked here is whether the processing party can assign the data to a natural person using further information. In practice, therefore, even data that is primarily only factual technical data will in certain cases be regarded as personal data.

The anonymization of data is therefore one way to exclude the applicability of data protection law. However, the high requirements that apply before data can be considered anonymous should not be underestimated. This only includes personal data that has been anonymized in such a way that the data subject cannot be identified or can no longer be identified.

Anonymization, which does not allow any inference to a natural person, must be distinguished from pseudonymization. This refers to personal data that can no longer be attributed to a specific individual without additional information, provided that this additional information is kept separately and is subject to technical and organizational measures to ensure that the personal data is not attributed to an identified or identifiable natural person.

This shows that the classification also depends on who actually collects the data. For example, the operator of a fleet of vehicles has different possibilities to assign factual data such as the movement data of the respective vehicles to specific persons, since he/she knows which vehicles are assigned to which person. For the operator, therefore, transaction data is regularly person-related, while, for example, a mechanical workshop reads the transaction data for the maintenance of the vehicles, but – depending on the circumstances of the individual case – often cannot assign it to a specific person.

What is “Privacy by design”, and how should it be implemented by car manufacturers?

“Privacy by design” is indeed a legal requirement under the GDPR, and has an impact right from the beginning of the product development process. As a result, vehicle manufacturers should take especial note of this. Privacy by design requires that appropriate technical and organizational measures – such as pseudonymization – should be taken, in order to effectively enforce principles of data protection law such as data minimization. Appropriate methods of technology design are thus intended to ensure that the requirements of the GDPR are taken into account and that the rights of the data subjects concerned are protected.

The respective applications in connected and autonomous mobility must therefore be technically designed from the outset in such a way that data protection-friendly presets ensure that, in principle, only the specific personal data that is necessary for the particular purpose of processing is processed. Let me give you a simple example: in order to avoid collisions with other road users, the systems must reliably detect cyclists or pedestrians, for instance. For this purpose, however, it is not necessary to be able to identify a pedestrian personally. The technical systems by which this is achieved are basically left to the manufacturer. A multitude of approaches can be considered here – up to and including technical designs through which the corresponding data is already anonymized at the time of collection.

In the context of such a complex ecosystem as connected mobility – with autonomous vehicles, public transport operators, share offers, ticketing and payment systems, etc. – how can data protection be implemented and ensured?

As just mentioned, the “privacy by default” and “privacy by design” principles are of particular importance in ensuring, through data protection-friendly presets, that only personal data whose processing is necessary for the particular purpose is processed.

This applies to the amount of personal data collected, the scope of processing, the storage period, and accessibility. Ideally, the applications for connected and autonomous mobility will be designed from the outset in such a way that as little personal data as possible is processed for the respective purposes. It should also be noted that the GDPR also lays down very far-reaching rules for the documentation and organization of data protection compliance.

In addition, according to the GDPR, any processing in the autonomous vehicle must be examined to determine whether the data protection rights of the data subject are likely to present a high risk. If this is the case, a comprehensive risk assessment must be carried out, for example, when a large amount of personal data concerning the whereabouts of natural persons is processed on the basis of location data. A data protection impact assessment must be carried out, for example, before certain processing activities start, e.g. for new forms of processing, in particular the use of new technologies and data processing with a high risk to rights and freedoms. This process also makes sense because, with the involvement of data protection authorities and data protection officers, appropriate security precautions can be developed at an early stage in order to prevent the violation of personal data.

Marco Müller-ter Jung, partner and specialist lawyer for IT law, works in Cologne. His main areas of expertise are IT law, intellectual property law, and data protection. After studying law in Düsseldorf, Marco Müller-ter Jung obtained his Master of Laws (LL.M., Information Law) at the Düsseldorf Law School in 2008 and was admitted to the bar in 2009. Before joining the DWF Germany law firm, he was a lawyer at the law firm Wülfing Zeuner Rechel.

Marco Müller-ter Jung advises national and international companies on Internet, eCommerce, and data protection law as well as on IT contracts and complex IT projects, such as the procurement and integration of new technologies, migration, and outsourcing. His focus lies in advising on the legal requirements of disruptive technologies, such as the Industrial Internet, autonomous driving, and voice assistance systems. In addition, Marco Müller-ter Jung is Vice Chair of the technical committee 105.5 "Legal Aspects of Additive Manufacturing" at the VDI.

Please note: The opinions expressed in Industry Insights published by dotmagazine are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of the publisher, eco – Association of the Internet Industry.